Nature has inspired the research and work behind geological disposal

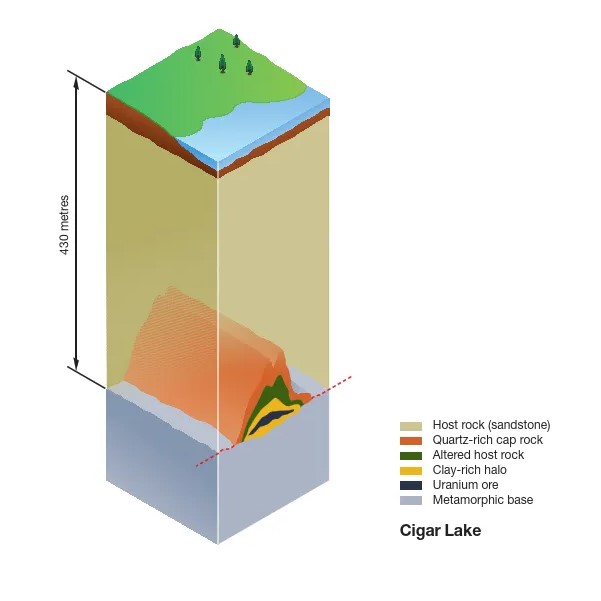

Cigar Lake is made up of many layers of different rock that help to contain the uranium ore deposit deep underground

In the uranium-rich Athabasca Basin of northern Saskatchewan, in Canada, there is an example of nature’s Geological Disposal Facility (GDF) This is the 1.3 billion-year-old Cigar Lake deposit.

It contains high-grade uranium ore, and it is about 450 metres (a third of a mile) below the surface and surrounded by thick clay. As a result, there are no traces of radioactive elements found above ground. Cigar Lake, is the world’s largest undeveloped uranium deposit where the uranium ore is securely housed in layers, including a clay-rich zone, a sandstone host rock, a quartz-rich cap and a metamorphic bedrock base.

Long-term safety

More than 42,000 tonnes (93 million pounds) of U308 uranium have been produced at Cigar Lake since it was commissioned in 2014. Nuclear Waste Services (NWS), which is assessing potential GDF sites across the UK, says that the deposit’s natural and safe storage provides confidence in the long-term safety of deep geological disposal.

NWS’s geological investigations will include rock type, structure, the potential impact of climate change, groundwater and previous activities in the areas, such as mining. The host rocks in which a GDF will be built need to have little or no groundwater movement through them. They also need to allow for the construction of tunnels.

NWS’s scientists and engineers have more than 30 years’ experience in research and development to support geological disposal, and they are assisted by community engagement teams.

All of the work carried out by NWS is regulated by the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and the Environment Agency (EA) in England, and scrutinised by the independent Committee on Radioactive Waste Management.